Как мы выявили мошеннический фонд

29 октября 2024

Управление Капиталом

29 октября 2024

Недавно наше внимание привлекло банкротство фонда Crаwford Ventures. В нем было всего 16 млн долл. и 45 инвесторов, но оно заслуживает весьма пристального внимания, потому что, на наш взгляд, банкротство было мошенничеством с самого начала, и на его примере можно поучиться распознавать мошенников.

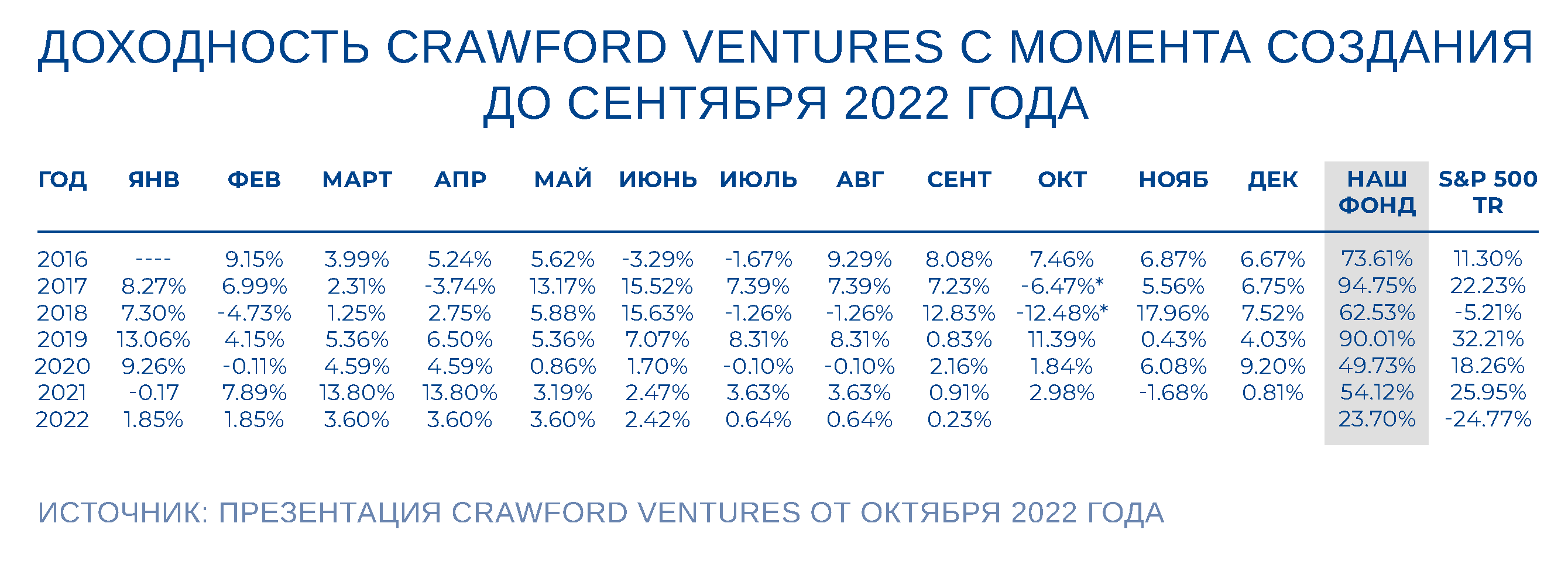

Фонд был создан в 2016 году и «зарабатывал» от 50 до 90% годовых, в основном торгуя валютами. Мы обнаружили его осенью 2022 года и сразу же поняли, что это, скорее всего, мошенничество, потому что столько на регулярной основе на торговле валютами не сделаешь. Однако мы поговорили с командой фонда — в качестве тренинга своих навыков по распознаванию мошенничества. В ходе разговора наша уверенность в том, что им руководят нечистые на руку люди, укрепилась. Мы ожидали, что нам предъявят рассказ о том, как фонд торгует самыми экзотическими парами валют, ведь высокую доходность проще сделать при высокой волатильности. (И мы бы все равно не поверили.) Но нет, они сказали, что торгуют парой «доллар/евро», а на ней, разумеется, систематически можно зарабатывать только менее 10% в год.

В сентябре 2024 года стало известно, что фонд показывал потенциальным инвесторам сфальсифицированные аудиторские заключения. Управляющие даже создали поддельный адрес аудиторской компании и сами писали от ее имени инвесторам. Аудитор был австралийский. Эван Кац (Evan H. Katz), один из партнеров компании, управлявшей фондом, был оштрафован Федеральной комиссией по ценным бумагам США примерно на 200 тысяч долларов. Почему на такую смехотворную сумму? Потому что он отстаивал позицию, что сам был введен в заблуждение двумя другими основателями компании, братьями Акшеем и Дэвом Камбожи (Akshay и Dev Kamboj), которые и вели весь бизнес, и его участие в мошенничестве не было доказано. Деятельность двух других сооснователей расследована, комиссия подала в суд, но решение по ним еще не вынесено. Мы полагаем, что мошенничество будет доказано.

В заключении Комиссии по ценным бумагам США говорится, что показанная на бумаге прибыль фонда в природе не существовала. На самом деле он потерял около 4 млн долл., или около 25% своего капитала. Всплыла информация, что Эван Кац уже был связан с фондами, которые занимались мошенничеством. Так в 2009 году он вложился в NIR Group, которая в 2011 году приостановила выплаты инвесторам. Комиссия по ценным бумагам усмотрела мошенничество в действиях управляющих при вложениях в частные (непубличные) компании и обнаружила использование средств инвесторов фонда в личных целях. (Мошенничать с непубличными компаниями всегда проще, потому что нет котировок, являющихся основанием оценки.) Фонд был очень большим, его активы на пике оценивались в 867 млн долларов.

У нас самих до биографии Каца дело не дошло, мы управляющих сочли недобросовестными и без этого. Однако в нашей практике был не один случай, когда мы до изучения биографий менеджеров с виду нормальных фондов доходили и отклоняли фонды по причине темных пятен в биографиях управляющих. Я вспоминаю таких три, в одном случае фонд обанкротился вскоре после того, как мы его отклонили.

Инвестиционное сообщество обратило внимание на то, что Кац продолжал рекламировать свой последний фонд еще в сентябре 2024 года, когда расследование в отношении него подходило к концу. В частности, он призывал вкладываться в фонд через 17 тысяч своих контактов на LinkedIn.

Что в этой ситуации радует? Да, кое-что может и радовать! Это размер второго фонда по сравнению с первым. В нем было всего 16 млн долларов, а инвесторов — 45, то есть на одного приходилось 355 тысяч долл. Это означает, что фонд покупали физлица — профессионалы обошли его стороной. По американским меркам денег удалось собрать совсем немного.

Какие уроки можно извлечь из этой истории? Очевидно, что профессионалы лучше умеют выявлять потенциальные угрозы мошенничества. Менеджер, который уже был замешан в непрозрачной деятельности, не должен проходить отбор, как бы он ни каялся, ни делал вид, что был ни при чем, и какую бы доходность он ни показывал в новом фонде.

Любая сверхдоходность должна настораживать. Доходности могут быть очень высокими, но этому должно быть объяснение. Самая высокая доходность, которую видели мы, — в пределах 35% годовых, но это при инвестировании в биотехнологические акции и при специализации на предсказании результатов клинических испытаний. Неудачные могут обрушить цену акций полностью, и наоборот — в случае успеха бумага может взлететь на сотни процентов. Суперсложная модель, которая предсказывает результат верно хотя бы в 55% случаев, может дать такую доходность. Источник доходов здесь понятен. Кроме того, высокая доходность может быть аномалией. Мы видели много фондов, которые в отдельные годы зарабатывали и 50%, и 60%, и даже 100%, но это, во-первых, особые годы (вроде кризисного 2008-го), и во-вторых, они не могут этого повторить. Стабильно высокий результат — сигнал опасности!

Для получения доходности необходимо принятие каких-то рисков. Не все риски вознаграждаются, и принятие большого риска — не гарантия высокой доходности, но если брать на себя минимальный риск, типа риска вложений в казначейские обязательства США, заработать можно только доходность, выражающуюся в однозначных цифрах.

Наконец, особенно тщательной проверке должны подвергаться фонды, вкладывающиеся в непубличные компании. И там репутация управляющего играет ключевую роль. В самих таких вложениях ничего плохого нет, они могут повысить доходность фондов, но мы, в частности в нашем фонде GEIST, все же избегаем вложений в фонды, где доля инвестиций в непубличные компании выше 2–3%. На всякий случай.

Не всегда награды свидетельствуют о качестве фонда. Crаwford Ventures собрал массу наград уважаемых институций. Но эти награды можно принимать во внимание только в совокупности с другими характеристиками фонда.

Зачем это знать

Если бы все случаи мошенничества были похожи на вышеописанный кейс, то сфера инвестиционных услуг была бы значительно более безопасной и процветающей. Обычно выявить недобросовестное поведение значительно сложнее. Продукты, обещающие баснословную доходность, с низкими рисками, только в самых качественных инструментах и с высокой ликвидностью, почти наверняка мошеннические и чаще всего не собирают много денег, ограничиваясь узкой целевой аудиторией непрофессиональных инвесторов.

Бóльшую опасность представляют продукты, результаты и параметры которых достаточно высоки, чтобы привлечь внимание, и весьма правдивы, чтобы не вызывать веских подозрений. Они могут существовать очень долго, собирать сотни миллионов долларов и также «разоряться» в один день, когда либо схема раскрыта, либо заканчивается приток новых денег, либо наступают события (например, резкая просадка рынков), которые могут послужить оправданием потери денег. Не обладая достаточным опытом, знаниями и ресурсами, финансовыми и временными, защититься от таких рисков невероятно сложно. Зная это, мошенники чаще всего таргетируют именно частных инвесторов.

Поделиться